Wednesday, May 16, 2007

On Leaving Nigeria

I love Nigeria. Having worked in this country off and on since 1995, I guess I would either have to love it or be one of the most mercenary workers in the world. Well, I admit it, the money has had a lot to do with my returning to work here for 28 days and then flying home on the longest commute in the world for my time off. But the people and friends I have made here are the major incentive for returning time after time to this very dysfunctional country.

To be sure, there have been a great many positive changes since I first set foot on West African soil some 12 years ago. The airport alone is the first major improvement one notices. Not only is the air conditioning comfortably cool throughout the building, the people movers actually work almost all of the time. The second improvement at the airport is the absence of would-be "helpers," scrambling to carry your bags for tips and there are absolutely no immigrations or customs officials with their hands out asking for dash money.

Until the recent elections, the roads were relatively easy to travel. There were no roadblocks of soldiers and policemen every few kilometers trying to extort money from passing vehicles. Once in 1997, when I was returning from a four-day trip to London, when I had to accompany a very sick American to the Hospital for Tropical Medicine there, my car was stopped when I returned. My driver, liaison and I were summarily removed from our vehicle and our the army lieutenant in charge asked to see my papers.

Unbeknown st to me, the military dictator at the time, General Sani Abacha, had arrested some of his generals a few days earlier and accused them of plotting a coup. Incidentally, the current president, for at least two more weeks, Obasanjo, was one of those generals arrested. At any rate, I was asked if I had returned to Nigeria to destabilize the government. Was I a CIA spy, the lieutenant wanted to know.

As our vehicle and my bags were searched, I tried to explain why I left and returned. Finally, a private pulled a stethoscope out of my bag and showed it to the lieutenant. "You are a doctor?" he asked.

"Yes I am," I answered in a Jon Lovitz tone of voice.

"Sorry for the misunderstanding, you may go," said the suddenly apologetic Nigerian officer.

I have worked very closely with some of the finest people I have ever known in Nigeria. I have been made an honorary chief, been given an Igbo name, and have been made to feel welcome and wanted by almost every regular Nigerian I have come in contact with. I've had the pleasure and honor of meeting Nobel laureate Wole Soyinka and I have had the privilege of working with some very dedicated and proficient Nigerian physicians and safety officers. I wish I could keep working here.

However, a combination of personal health considerations and the increased actions of a militancy I find myself for the most part in total agreement with, have forced me to tender my resignation to the company I am consulting with. It is truly with a heavy heart that I physically take leave of Nigeria on May 31. My soul and spirit will never leave this country though and I hope to return here when their is a more equitable and just government run by statesmen instead of arrogant goons who care only for themselves.

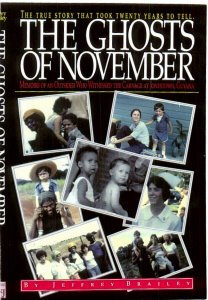

I plan to write a book about my experiences in Nigeria. I am told this book is part of my destiny and it will change the core of how things are done in this country. I don't really know if I have the wherewithal to accomplish this or not. I am no where near the point where I feel I can start such a monumental project. Maybe leaving Nigeria will provide me prospective.

To be sure, there have been a great many positive changes since I first set foot on West African soil some 12 years ago. The airport alone is the first major improvement one notices. Not only is the air conditioning comfortably cool throughout the building, the people movers actually work almost all of the time. The second improvement at the airport is the absence of would-be "helpers," scrambling to carry your bags for tips and there are absolutely no immigrations or customs officials with their hands out asking for dash money.

Until the recent elections, the roads were relatively easy to travel. There were no roadblocks of soldiers and policemen every few kilometers trying to extort money from passing vehicles. Once in 1997, when I was returning from a four-day trip to London, when I had to accompany a very sick American to the Hospital for Tropical Medicine there, my car was stopped when I returned. My driver, liaison and I were summarily removed from our vehicle and our the army lieutenant in charge asked to see my papers.

Unbeknown st to me, the military dictator at the time, General Sani Abacha, had arrested some of his generals a few days earlier and accused them of plotting a coup. Incidentally, the current president, for at least two more weeks, Obasanjo, was one of those generals arrested. At any rate, I was asked if I had returned to Nigeria to destabilize the government. Was I a CIA spy, the lieutenant wanted to know.

As our vehicle and my bags were searched, I tried to explain why I left and returned. Finally, a private pulled a stethoscope out of my bag and showed it to the lieutenant. "You are a doctor?" he asked.

"Yes I am," I answered in a Jon Lovitz tone of voice.

"Sorry for the misunderstanding, you may go," said the suddenly apologetic Nigerian officer.

I have worked very closely with some of the finest people I have ever known in Nigeria. I have been made an honorary chief, been given an Igbo name, and have been made to feel welcome and wanted by almost every regular Nigerian I have come in contact with. I've had the pleasure and honor of meeting Nobel laureate Wole Soyinka and I have had the privilege of working with some very dedicated and proficient Nigerian physicians and safety officers. I wish I could keep working here.

However, a combination of personal health considerations and the increased actions of a militancy I find myself for the most part in total agreement with, have forced me to tender my resignation to the company I am consulting with. It is truly with a heavy heart that I physically take leave of Nigeria on May 31. My soul and spirit will never leave this country though and I hope to return here when their is a more equitable and just government run by statesmen instead of arrogant goons who care only for themselves.

I plan to write a book about my experiences in Nigeria. I am told this book is part of my destiny and it will change the core of how things are done in this country. I don't really know if I have the wherewithal to accomplish this or not. I am no where near the point where I feel I can start such a monumental project. Maybe leaving Nigeria will provide me prospective.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment