Friday, May 4, 2007

The Anniversary Syndrome

(I wrote this essay for the Jonestown Institute's annual newsletter a couple of years ago.)

There was a time when I did not believe in Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). Part of the reason for my skepticism may be that I was a professional soldier, and psychological disorders, particularly this one, were often considered career-enders.

I served two tours in Vietnam as a medic with the 85th Evacuation Hospital. I worked a minimum of 12 hours a day, seven days a week on the Recovery Room/Intensive Care Unit. It was not pleasant duty. Day after interminable day, we treated American soldiers, airmen and marines with horrendous wounds of war, civilian women and children who had grotesque burns or missing limbs and enemy prisoners-of-war with wounds so severe, we often were barely able to put them back together again.

Every day represented a new and different assault on the psyche of medics serving on the line or in hospitals. I'd like to believe it was the innate compassion most medical personnel possess that allowed me to perform agonizing duties with professional acumen and the psychological detachment necessary to remain reasonably sane.

Despite these experiences, I did not exhibit any symptoms of PTSD when I returned to the U.S. after my tours in Vietnam. In fact, when I would hear or read about fellow soldiers or vets who acted out in an inappropriate manner, ostensibly because of the trauma they experienced during the war, I considered them frauds or weaklings who were probably psychologically flawed before entering the military. It wasn't until many years later that I recognized exactly how complicated and fragile the mind is.

In 1978, I was confronted by an event so disturbing and so massive in scope that it caused me psychological distress that continues to have an effect on my life to this day. I spent nine days in November of that year as senior medic of the Joint Humanitarian Task Force sent to Guyana to recover the remains of the victims of the Jonestown Massacre.

I was part of a team of about three dozen men and women who were deployed to Guyana on November 20, two days after the deaths. The event that had occurred there happened in an extremely hot tropical climate that caused all sorts of complications for body retrieval, identification, and removal. We also worked under incredible time constraints, since the conditions that hastened body decomposition served to create a very real physical health hazard for our team. Beyond that, the mental strain was almost overwhelming.

To this day, 25 years later, after being afflicted with Parkinson's Disease, after going in and out of states of homelessness for the past five years, after two divorces, and after fighting a powerful gambling addiction, I still consider the nine days spent in Guyana as the worst period of my life.

Yet, immediately after it was over and I returned to my duty station in the Panama Canal, my life seemed to return to normal. For a year, I rarely talked about or even thought about the Jonestown Massacre and my connection to it.

However, as ordinary as my life was during the weeks and months subsequent to this unprecedented military mission, there was a tiny seed of trouble hidden deep within my psyche waiting to emerge and disturb my conscious life. It happened very suddenly and dramatically.

That bad seed began to sprout almost exactly a year of my journey to and from the hell that was Jonestown. It was a Sunday in November 1979. I was walking past the bakery in Balboa, Panama on a peaceful pleasant morning. Delectable aromas were wafting from the open door of the shop, enticing customers to come in and buy the sweet breads and pastries it was famous for. But my olfactory nerves interpreted the odor as being the sickeningly sweet smell created by 914 bodies rotting in the tropical heat. I immediately vomited on the sidewalk.

Embarrassed by this reaction I had no control over, I dashed to my car and quickly returned home. Although not consciously aware of any changes to my normal behavior, I am told that for the next two weeks I was uncharacteristically moody and depressed. I cried for no apparent reason, argued with my spouse over petty and inconsequential grievances and treated my children with impatience and indifference.

My nights were marked by difficulty in falling to sleep and then abruptly waking up in a cold sweat after experiencing very realistic nightmares that resembled scenes from the classic horror film, Night of the Living Dead. It was as if the former residents of Jonestown were literally visiting me. Sleep was not a pleasant restful pastime during the next two weeks.

Just as suddenly as my bizarre behavior manifested itself, it disappeared. My wife and children who had spent a fortnight being cautious and tentative in dealing with me, slowly realized I was my old self again. Life was back to normal again until the following November when the symptoms returned for two weeks.

My family put up with these annual changes for five more Novembers until I finally achieved an epiphany provided by a very unlikely person at a very unusual location. My bowling team at Fort Sill, Oklahoma was participating in our weekly Tuesday night league game. It was my turn to bowl and I picked my ball up from the rack, approached the lane, released the ball and delivered a rare, for me, strike.

Rather than reacting joyously to this happy feat by shouting and issuing traditional high-fives to my teammates, I simply went back to my seat and sat down.

"Brailey, you don't bowl enough strikes that you should be that nonchalant," asked a member of my team who happened to be a psychologist. "What's the matter with you?"

"Nothing," I replied flatly.

Later, over pie and coffee with our spouses, the psychologist looked at me and said, "Do you feel all right? You look pretty depressed."

"I'm fine," I responded, not really realizing nothing could be further from the truth.

"No, he's not," said my Vietnamese wife. "He gets like this around Thanksgiving since he came back from Jonestown."

I am sure a 1000-watt halogen light bulb literally appeared over my head as I heard my wife's pronouncement and consciously recognized that I was indeed weird every November. My psychologist teammate told me to stop by his office the next morning.

He and I spent several hours that week discussing my behavior, its causes and means to control it. I came to learn I had a form of PTSD called "Anniversary Syndrome." It seems people affected by severe emotionally traumatic events are capable of suppressing them for most of the year, but when the date of the event looms annually, it triggers something within the brain that causes one to relive the terrible time.

After a relatively short period of informal therapy sessions, I succeeded in overcoming the bizarre behavior that plagued me for six Novembers. I was actually able to file my Jonestown experiences deep within the recesses of my brain and keep them from surfacing for the next 14 years.

I was a newlywed in February 1998. My second wife and I married on Valentine's Day. A couple of weeks later, we were sitting on our patio drinking coffee on a sunny Saturday morning. The portable phone rang and I answered with a cheery "Hello."

"Hello. My name is Jim Hougan. I am producing a documentary about Jonestown, and I'm looking for Jeff Brailey," a voice on the other end of the line said.

The hair on the nape of my neck stood up as I heard the word "Jonestown" for the first time in about a dozen years. "How did you find me?" I asked cautiously.

"Your name is on the list of soldiers who were on the Joint Humanitarian Task Force and I did an Internet search on your name and found your website. Are you the same Jeff Brailey?" Hougan asked.

I admitted it, and we spent the next 20 minutes chatting about my experiences in Guyana. I agreed to appear in the documentary, and Hougan said he'd come to San Antonio or send me an airline ticket to a city where he would tape the interview.

As I hung up the phone, my bride who had listened to my side of the conversation with wide-eyed curiosity, asked what I was talking about. I told her, "Jonestown."

"You were there?" she asked.

"Yes." I replied.

"IN THE CULT!?!?" she shouted.

"No, part of the cleanup," I said.

We spent the next few hours discussing the massacre and then went on to enjoy the remainder of our Saturday. That night, my wife shook me awake from a restless sleep. I asked why she had woken me up. "Because you were screaming in your sleep," she replied with a look of fear on her face.

"Uh oh, they're back," I said resignedly.

"Who's back," she asked.

"The ghosts," said I.

I went on to explain the Anniversary Syndrome that had bothered me years before. But this was February, not November, and I was a little rattled by it.

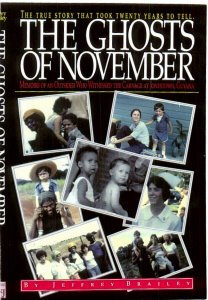

It was that very night The Ghosts of November: Memoirs of an Outsider Who Witnessed the Carnage at Jonestown, Guyana was conceived. It was my wife's idea that if I wrote about it, the ghosts would go away. I wrote the book in four months. It was published and released by J&J Publishers on October 31, 1998.

Writing the account of my nine days in Guyana, appearing on radio talk and television news shows, speaking at book signings and to civic groups, all were cathartic experiences that seem to have exorcised my ghosts for the time being.

Anniversary Syndrome is not the only ill-effect that Jonestown had on my life. Although I was brought up in the church and attended a Christian college, my spiritual life has never been the same. I still consider myself a Christian, but I am a very cynical nontrusting one.

While I still have a belief in God, my faith has been shattered. I will not trust His self-appointed representatives. It was not long after Jonestown that Jim and Tammy Bakker's sins against their flock were exposed, that Jimmy Swaggart tearfully confessed his infidelities, that Oral Roberts conned thousands of his followers into sending him millions of dollars so God would not "take him home," and that Robert Tilton was caught bilking gullible elderly Christians living on fixed incomes out of their money.

I began equating the antics of God's conmen with the evil deeds of Jim Jones that culminated in the taking of 914 lives in Jonestown. In my mind, most television evangelists are no better than he was, and the only thing that separates them from him is the fact that they have not become homicidal maniacs – yet.

Jonestown represents the impetus of my self-exile from organized religion, and phony television evangelists continue to provide me with plenty of reasons to continue to eschew the church.

Benny Hinn gives me the creeps, especially since I know he is a charlatan and fraud, yet the faithful continue to flock to and contribute to his dog-and-pony healing shows. Trinity Broadcasting and its boss, holy roller Paul Crouch, remind me of the power and charisma which Jim Jones used to control people. There are many more greedy and corrupt ministers using the media to make themselves rich.

Jonestown has alienated me from God. I suppose you could say this is evidence that far from being the God he claimed to be, Jones was actually Satan's servant.

At one time I believed that no matter how bad something turned out, there was always something to learn from every human experience, that some good would come from it, no matter how seemingly devastating the immediate outcome of it was. When I look back at the nine days I spent in Jonestown and the monumentally evil deeds that caused me to go there, I can honestly say I find no redeeming value in that experience.

There was a time when I did not believe in Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). Part of the reason for my skepticism may be that I was a professional soldier, and psychological disorders, particularly this one, were often considered career-enders.

I served two tours in Vietnam as a medic with the 85th Evacuation Hospital. I worked a minimum of 12 hours a day, seven days a week on the Recovery Room/Intensive Care Unit. It was not pleasant duty. Day after interminable day, we treated American soldiers, airmen and marines with horrendous wounds of war, civilian women and children who had grotesque burns or missing limbs and enemy prisoners-of-war with wounds so severe, we often were barely able to put them back together again.

Every day represented a new and different assault on the psyche of medics serving on the line or in hospitals. I'd like to believe it was the innate compassion most medical personnel possess that allowed me to perform agonizing duties with professional acumen and the psychological detachment necessary to remain reasonably sane.

Despite these experiences, I did not exhibit any symptoms of PTSD when I returned to the U.S. after my tours in Vietnam. In fact, when I would hear or read about fellow soldiers or vets who acted out in an inappropriate manner, ostensibly because of the trauma they experienced during the war, I considered them frauds or weaklings who were probably psychologically flawed before entering the military. It wasn't until many years later that I recognized exactly how complicated and fragile the mind is.

In 1978, I was confronted by an event so disturbing and so massive in scope that it caused me psychological distress that continues to have an effect on my life to this day. I spent nine days in November of that year as senior medic of the Joint Humanitarian Task Force sent to Guyana to recover the remains of the victims of the Jonestown Massacre.

I was part of a team of about three dozen men and women who were deployed to Guyana on November 20, two days after the deaths. The event that had occurred there happened in an extremely hot tropical climate that caused all sorts of complications for body retrieval, identification, and removal. We also worked under incredible time constraints, since the conditions that hastened body decomposition served to create a very real physical health hazard for our team. Beyond that, the mental strain was almost overwhelming.

To this day, 25 years later, after being afflicted with Parkinson's Disease, after going in and out of states of homelessness for the past five years, after two divorces, and after fighting a powerful gambling addiction, I still consider the nine days spent in Guyana as the worst period of my life.

Yet, immediately after it was over and I returned to my duty station in the Panama Canal, my life seemed to return to normal. For a year, I rarely talked about or even thought about the Jonestown Massacre and my connection to it.

However, as ordinary as my life was during the weeks and months subsequent to this unprecedented military mission, there was a tiny seed of trouble hidden deep within my psyche waiting to emerge and disturb my conscious life. It happened very suddenly and dramatically.

That bad seed began to sprout almost exactly a year of my journey to and from the hell that was Jonestown. It was a Sunday in November 1979. I was walking past the bakery in Balboa, Panama on a peaceful pleasant morning. Delectable aromas were wafting from the open door of the shop, enticing customers to come in and buy the sweet breads and pastries it was famous for. But my olfactory nerves interpreted the odor as being the sickeningly sweet smell created by 914 bodies rotting in the tropical heat. I immediately vomited on the sidewalk.

Embarrassed by this reaction I had no control over, I dashed to my car and quickly returned home. Although not consciously aware of any changes to my normal behavior, I am told that for the next two weeks I was uncharacteristically moody and depressed. I cried for no apparent reason, argued with my spouse over petty and inconsequential grievances and treated my children with impatience and indifference.

My nights were marked by difficulty in falling to sleep and then abruptly waking up in a cold sweat after experiencing very realistic nightmares that resembled scenes from the classic horror film, Night of the Living Dead. It was as if the former residents of Jonestown were literally visiting me. Sleep was not a pleasant restful pastime during the next two weeks.

Just as suddenly as my bizarre behavior manifested itself, it disappeared. My wife and children who had spent a fortnight being cautious and tentative in dealing with me, slowly realized I was my old self again. Life was back to normal again until the following November when the symptoms returned for two weeks.

My family put up with these annual changes for five more Novembers until I finally achieved an epiphany provided by a very unlikely person at a very unusual location. My bowling team at Fort Sill, Oklahoma was participating in our weekly Tuesday night league game. It was my turn to bowl and I picked my ball up from the rack, approached the lane, released the ball and delivered a rare, for me, strike.

Rather than reacting joyously to this happy feat by shouting and issuing traditional high-fives to my teammates, I simply went back to my seat and sat down.

"Brailey, you don't bowl enough strikes that you should be that nonchalant," asked a member of my team who happened to be a psychologist. "What's the matter with you?"

"Nothing," I replied flatly.

Later, over pie and coffee with our spouses, the psychologist looked at me and said, "Do you feel all right? You look pretty depressed."

"I'm fine," I responded, not really realizing nothing could be further from the truth.

"No, he's not," said my Vietnamese wife. "He gets like this around Thanksgiving since he came back from Jonestown."

I am sure a 1000-watt halogen light bulb literally appeared over my head as I heard my wife's pronouncement and consciously recognized that I was indeed weird every November. My psychologist teammate told me to stop by his office the next morning.

He and I spent several hours that week discussing my behavior, its causes and means to control it. I came to learn I had a form of PTSD called "Anniversary Syndrome." It seems people affected by severe emotionally traumatic events are capable of suppressing them for most of the year, but when the date of the event looms annually, it triggers something within the brain that causes one to relive the terrible time.

After a relatively short period of informal therapy sessions, I succeeded in overcoming the bizarre behavior that plagued me for six Novembers. I was actually able to file my Jonestown experiences deep within the recesses of my brain and keep them from surfacing for the next 14 years.

I was a newlywed in February 1998. My second wife and I married on Valentine's Day. A couple of weeks later, we were sitting on our patio drinking coffee on a sunny Saturday morning. The portable phone rang and I answered with a cheery "Hello."

"Hello. My name is Jim Hougan. I am producing a documentary about Jonestown, and I'm looking for Jeff Brailey," a voice on the other end of the line said.

The hair on the nape of my neck stood up as I heard the word "Jonestown" for the first time in about a dozen years. "How did you find me?" I asked cautiously.

"Your name is on the list of soldiers who were on the Joint Humanitarian Task Force and I did an Internet search on your name and found your website. Are you the same Jeff Brailey?" Hougan asked.

I admitted it, and we spent the next 20 minutes chatting about my experiences in Guyana. I agreed to appear in the documentary, and Hougan said he'd come to San Antonio or send me an airline ticket to a city where he would tape the interview.

As I hung up the phone, my bride who had listened to my side of the conversation with wide-eyed curiosity, asked what I was talking about. I told her, "Jonestown."

"You were there?" she asked.

"Yes." I replied.

"IN THE CULT!?!?" she shouted.

"No, part of the cleanup," I said.

We spent the next few hours discussing the massacre and then went on to enjoy the remainder of our Saturday. That night, my wife shook me awake from a restless sleep. I asked why she had woken me up. "Because you were screaming in your sleep," she replied with a look of fear on her face.

"Uh oh, they're back," I said resignedly.

"Who's back," she asked.

"The ghosts," said I.

I went on to explain the Anniversary Syndrome that had bothered me years before. But this was February, not November, and I was a little rattled by it.

It was that very night The Ghosts of November: Memoirs of an Outsider Who Witnessed the Carnage at Jonestown, Guyana was conceived. It was my wife's idea that if I wrote about it, the ghosts would go away. I wrote the book in four months. It was published and released by J&J Publishers on October 31, 1998.

Writing the account of my nine days in Guyana, appearing on radio talk and television news shows, speaking at book signings and to civic groups, all were cathartic experiences that seem to have exorcised my ghosts for the time being.

Anniversary Syndrome is not the only ill-effect that Jonestown had on my life. Although I was brought up in the church and attended a Christian college, my spiritual life has never been the same. I still consider myself a Christian, but I am a very cynical nontrusting one.

While I still have a belief in God, my faith has been shattered. I will not trust His self-appointed representatives. It was not long after Jonestown that Jim and Tammy Bakker's sins against their flock were exposed, that Jimmy Swaggart tearfully confessed his infidelities, that Oral Roberts conned thousands of his followers into sending him millions of dollars so God would not "take him home," and that Robert Tilton was caught bilking gullible elderly Christians living on fixed incomes out of their money.

I began equating the antics of God's conmen with the evil deeds of Jim Jones that culminated in the taking of 914 lives in Jonestown. In my mind, most television evangelists are no better than he was, and the only thing that separates them from him is the fact that they have not become homicidal maniacs – yet.

Jonestown represents the impetus of my self-exile from organized religion, and phony television evangelists continue to provide me with plenty of reasons to continue to eschew the church.

Benny Hinn gives me the creeps, especially since I know he is a charlatan and fraud, yet the faithful continue to flock to and contribute to his dog-and-pony healing shows. Trinity Broadcasting and its boss, holy roller Paul Crouch, remind me of the power and charisma which Jim Jones used to control people. There are many more greedy and corrupt ministers using the media to make themselves rich.

Jonestown has alienated me from God. I suppose you could say this is evidence that far from being the God he claimed to be, Jones was actually Satan's servant.

At one time I believed that no matter how bad something turned out, there was always something to learn from every human experience, that some good would come from it, no matter how seemingly devastating the immediate outcome of it was. When I look back at the nine days I spent in Jonestown and the monumentally evil deeds that caused me to go there, I can honestly say I find no redeeming value in that experience.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment