Wednesday, September 10, 2008

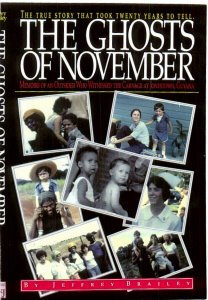

Chapter Nine

Chapter Nine: “He has a heat Rash”

“I love the man that can smile in trouble, that can gather strength from distress, and grow brave by reflection. ‘Tis the business of little minds to shrink, but he whose heart is firm, and whose conscience approves his conduct, will pursue his principles unto death.”

Thomas Paine

I served in the U.S. Army for 20 years. I spent time in several poor countries but Guyana was perhaps the most impoverished nation I ever visited. There is one sure sign of a country’s wealth or lack of it – the amount of litter you find along its roadways.

The more prosperous a people, the more litter that is accumulated along its highways. Nigeria has tons of trash everywhere. The country is basically one big trash dump. Now there are a lot of poor people in that West African nation, but there are a lot of wealthy ones too.

Matthews Ridge, Guyana has got to be one of the poorest places on earth. Every bit of waste in the small town was recycled, not out of any great concern for the environment, but out of necessity. Empty tin cans became patches for leaky roofs or walls. Waste paper was collected and used to start cook fires.

Matthews Ridge is a formerly bustling town built near what had become depleted bauxite minds in northwest Guyana, near the frontier border with Venezuela. During its heyday, some five years before the arrival of the Jonestown Agricultural Commune in 1976, Matthews Ridge boasted a population of more than a 1000 miners and their families.[1] By the time Jonestown’s residents perished in the mass murder/suicide, the town had shrunk to about 250, mostly Amerindian residents.

The main industry of the former mining town became subsistence farming and by 1978, the farmers and their families were barely surviving. Sadly, there were more bars in Matthews Ridge than all other businesses combined.

Our aid station was set up at an airfield three miles south of Matthews Ridge. The only people living at that location was a garrison of 20 or so Guyana Defense Force soldiers who lived and worked in three small buildings situated on a small mesa overlooking the black tarmac runway. We shared a small corner of the flat hill with the GDF troopers.

There was one small building on the edge of the tarmac. It was little more than a shack with a large overhanging roof, used to shelter travelers from the weather, be it the incessant heat of the tropical sun or the persistent showers of the two four-month rainy seasons of the region. Our Army fuel specialists took over this building as their fuel station.

Two signs adorned the shack. One announced the name of the town to any transients passing through who weren’t sure where they were. The other told travelers to the region they had entered a malaria area and were required to check in with the local Malaria Control Office.

We interacted daily with the GDF soldiers whose mesa we shared and the civilians of the small town down the road. Since our daily fare of c-rations quickly became boring and the locals had never seen such foods, we managed to trade some of our military-issued meals for locally produced bread and cheese. Freshly baked Matthews Ridge bread and native cheese was still a cold meal, but at least it was a different and tasty change to our diet.

But something happened on Thanksgiving Day that made our already cordial relationship with the soldiers and civilians even friendlier. By 1800 hours, we realized our promised Thanksgiving hot dinner was not going to materialize. The thought of eating beans and franks for Thanksgiving instead of the promised turkey with all the fixings was depressing to say the least.

Our Air Force communications sergeant radioed the task force headquarters at Timheri Airport to inquire about the promised and eagerly anticipated first hot meal in Guyana that failed to appear on our table. The duty officer at headquarters promised to look into the matter. Some 30 minutes later, he informed us that apparently there had been a snafu in the delivery of our Thanksgiving dinner and the duty officer promised he would rectify the situation. He said for us to look for arrival of a holiday dinner with all the fixings the next morning. He then asked how many people were at our location and we answered honestly, eight.

The next morning, Sanborn and Bernal, two famous gourmets, were waiting impatiently at the airfield shack. Finally, at 0900 hours, a UH-1 helicopter dropped out of the sky. The bird’s crew chief motioned for Sanborn and Bernal to approach the aircraft and the two soldiers, walking briskly, bodies crouching to avoid the rotor blades, did just that. They picked up two big boxes and had to make two more trips to the chopper to pick up four more containers of food.

Six large boxes of Thanksgiving dinner for eight servicemen? We were hungry and looking forward to the promised feast, but this was a little much!

The rest of the team bound down the hill to the shack. We all brought the boxes back to the aid station. Sanborn opened the first box. It was like kids opening presents on Christmas morning. “Half pints of milk! There must be a hundred of them,” said Sanborn.

“These two boxes got TV dinners, Jeff,” said Bernal. “How many?” I asked.

“Eighty eight, I count 88,” said Fielder.

“Bunch of fruit and nuts in this box,” said Sanborn.

Snafus are not isolated incidents in the Army, but rarely is a foul up followed by a snafu as positive as this one was. We were blessed with 80 extra meals.

Sanborn and Bernal wanted to dig in and pig out. They wanted to see how big of a dent eight hungry soldiers could put in this huge cache of food. Saner heads prevailed however, after Fielder suggested we invite the local GDF garrison and some of the locals, mostly female of course, to partake in our Thanksgiving Day feast. Some of the kids were already hanging around and Fielder told them to go round up their friends for a celebration. I walked over to the GDF outpost and invited Sergeant Harper and his comrades to our holiday dinner.

So on November 24, 1978, a day after the football games were played and most Americans were finished digesting their Thanksgiving feast of the day before, eight American servicemen, far from home, taught two dozen Guyanese Defense Force soldier and twice that many local teenaged girls about one of their country’s most popular holidays. I guess the meal was not unlike the first Thanksgiving celebration more than 300 years earlier, when the colonists invited the Native Americans to share their bounty.

This gesture, which in reality was actually a way to keep good food from being wasted, solidified the friendships we already formed with the soldiers and young people of Matthews Ridge. What had begun purely by serendipity with John Wayne bars on Monday, was cemented on Friday by Specialist Fourth Class Randy Fielder, who, I’ve got to believe, did so with some degree of calculation. The young man had become very friendly with not just a few of the black beauties of Matthews Ridge during the short time he was there.

Although they had little of value to share with us, the people of Matthews Ridge gave us more than they realized. They were among the kindest and most generous folks I ever met. From the man who walked three miles from his home to the airstrip with me on that dark night, to the friends Sanborn and Fielder made, to Pauline’s grandfather and mother, everyone we came in contact with represented the finest in humankind.

One night, while I was sitting in Mrs. Pool’s bar drinking a cold Banks Beer, a young man approached me. As he took the seat next to mine, he pulled a handful of Polaroid pictures from his pocket and spread them on the bar in front of me. He told me he had shot the photos around two weeks earlier, while visiting Jonestown.

The young man was fairly clean cut. He could easily have passed for an African-American on any college campus in the States, save for his obvious Guyanese accent.

I looked began looking at the pictures before me and asked questions as I viewed each one. The minister of transportation and other politicos appeared in a few shots. The local GDF commander was in some others. A smiling Jim Jones was usually in each shot that had dignitaries in it. There were some photos that showed Jones alone with a tree or a prop. There was even a picture of a bee hive. The Jonestown band was in one of the pictures and happy dancing teenagers were in another. These images made me wonder out loud what could have caused these seemingly free-spirited American expatriates to participate in the mass murder/suicide that took their lives.

After studying and discussing each of the instant photos with the friendly owner of them, I restacked the lot of them and handed them back to the young man.

“No,no,” he said, sliding the stack back in front of me. “They are for you, a gift.”

“Oh no,” I replied, realizing the potential value of the photos. “I could not take them.”

“Please, I wish you to have them,” he said.

Not wishing to offend this earnest young man, I told him I would take the photos only if he allowed me to pay for the film. In the United States, Polaroid film was quite expensive. I could only imagine how much of a financial investment these 20 pictures might represent in Guyana.

Finally, after several minutes of protest, the young man accepted my offer of 10 American dollars for the 20 photos. After arriving back at the aid station that night, I reviewed the set of pictures and decided to try to sell them to the news media when I returned to Panama. I didn’t realize at the time the grief these Polaroids would cause me.

The duty at Matthews Ridge became so routine that boredom was the biggest challenge we had to overcome. The anticipated poisoning victims were long dead before we even arrived in Guyana. The few medical problems experienced by the GREGG team and their support personnel in Jonestown were easily managed by the Special Forces medic on the ground there.

Our days were filled with administrative duties and “make work” tasks. We inventoried supplies and equipment more in those nine days than we did in the previous nine months in Panama. I made a few day trips into Jonestown, more as a diversion than to accomplish any mission-essential task. We all became competent radio operators by assisting the two Air Force communication specialists.

Our own Mike Sanborn became the only actual medical emergency our aid station cared for during the entire nine days we stayed at Matthews Ridge and this happened on our last day at the airstrip.

It was the morning of November 28, the final day the GREGG team would be in Jonestown. The remains of all the adult victims and two-thirds of the children had already been removed from the commune. We had been alerted early that morning that an aircraft would arrive in the early afternoon to transport us and our equipment to Timheri Airport in Georgetown.

As soon as Bernal, who was on radio watch, informed us of our move out order, we broke down our supplies and equipment. Specialist Fourth Class Michael Sanborn, 20-years-old and endowed with more muscle than common sense, removed his field jacket and olive drab t-shirt and took down our two tents. So intent was he on going home, he didn’t heed my warning to put his shirts back on and to slow down.

Within an hour, Sanborn was noticeably ill. He perspired so profusely that his trousers were thoroughly soaked in sweat. He appeared very weak and pale. I ordered the young medic to sit in the shade of our sleep tent that was still standing. His skin was cool and clammy and his blood pressure was extremely low.

I also noted that Sanborn’s entire torso and arms were covered with small, red, raised lesions. He obviously was suffering from heat exhaustion complicated by miliaria rubra, or what is commonly called “prickly heat” or “heat rash.”

Either problem alone can be easily managed. While heat exhaustion is a debilitating medical problem, when properly treated with rest and oral fluids, it is quickly reversed. However, when complicated by maliaria, which inhibits the sweat glands from functioning to cool the body properly, the combination of conditions constitute a possible life-threatening medical emergency.

I instructed Randy Fielder to cool Sanborn with tepid sponge baths and to offer him as much cool water as he coud drink. I told Sam Bernal to prepare an intravenous infusion of normal saline for Sanborn while I went to the radio to consult with our brigade surgeon, Major Burgos, at Timheri Airport.

Once we contacted the task force headquarters, the communications specialist there told us to wait while he sent for a doctor from the medical clearing station that was set up there. After about ten minutes that seemed like an eternity, the distant voice of a physician I didn’t know came through the speaker of our radio. While the quality of the voice was understandable, the doctor’s speech had an unmistakable slur to it that told me the good doctor had been imbibing at this early hour of the day.

“Thish ish Doctor Winston, how can I hep you?” said the tinny voice.

“Say ‘over,’ sir” prompted the communications specialist at the airport 150 miles away. “Over,” added the physician, obviously unfamiliar with radio protocol.

“Doctor,” I said, “I have an otherwise healthy, conscious 20-year-old Caucasian male with symptoms of severe heat exhaustion complicated by miliaria rubra of the trunk and arms.”

Worried that the quality of the radio speaker might cause the already mentally impaired physician to misunderstand what I was saying, I spelled the condition phonetically, “That’s miliaria, MIKE-INDIA-LIMA-INDIA-ALPHA-ROMEO-INDIA-ALPHA, over.”

There was a long pause from the Timheri Airport end of the radio call. I continued with my message: “His temperature is normal, pulse is 122, respirations 32, blood pressure 92 over 40. I have begun cooling the patient. We are giving him oral fluids and having him lay in the shade with his legs elevated. We have just started an IV of normal saline. Do you have any other instructions? Over.” The words were presented over the radio in slow distinct segments so the radio man could copy them down.

“What did you say he hash?” queried Doctor Winston.

“Say ‘over,’ sir,” coached the exasperated radioman.

“Over.”

“He has heat exhaustion and miliaria, I spell phonetically, MIKE-INDIA-LIMA-INDIA-ALPHA-ROMEO-INDIA-ALPHA, over,” I replied clearly and slowly. There was another long pause.

After what seemed like five minutes, but what was probably more like two, Doctor Winston’s beery voice boomed over the speaker of our radio. “Have him rest. Give him water to drink and start an IV. I want you to bring the patient here. Over,” he said in a slurred but authoritative voice.

While the Air Force communications sergeant arranged an air evacuation for Mike, I met quickly with Sam and Randy. Most of our equipment and supplies had already been packed and palletized. There was nothing left to do but take down one tent and wait for transportation to arrive. I told my two comrades I would accompany Sanborn to the clearing station at Timheri Airport.

Within 30 minutes, an Army U-21 arrived to transport Sanborn and me out of Matthews Ridge. While winging our way toward the airport, 150 miles away, I noticed the speed of the aircraft was well into the red warning area on the control panel speed gauge. I told the pilot that our emergency was not so severe that he had to risk flying faster than was safe, and he told me to take care of my patient and he would take care of flying the plane.

We did arrive safely at Timheri Airport. Medics from the clearing station sent down from Fort Bragg, North Carolina, met us and took Sanborn to a waiting field ambulance for transport to the medical units Admission & Disposition Section. I saw Captain Skinner and Major Burgos standing in an open doorway at the old terminal building, so I walked over to them to give them a report.

As I related the details of Sanborn’s heat injury and the difficult time I had communicating with the clearing station physician, an obviously soused Army lieutenant colonel physician approached and asked if I was the medic who brought the patient with the heat injury. I acknowledged I was and the arrogant doctor with the drinking problem looked at me and said derisively, “He doesn’t have malaria, he has a heat rash!”

All I could manage to respond was, “Yes sir, thank you sir, I’ve learned a lot from you today.” The tipsy doctor turned around and stumbled back to his clearing station.“He’s been like this every day,” said Major Burgos, by way of explaining Doctor Winston’s behavior.

[1] Tim Merrill, Ibid.

“I love the man that can smile in trouble, that can gather strength from distress, and grow brave by reflection. ‘Tis the business of little minds to shrink, but he whose heart is firm, and whose conscience approves his conduct, will pursue his principles unto death.”

Thomas Paine

I served in the U.S. Army for 20 years. I spent time in several poor countries but Guyana was perhaps the most impoverished nation I ever visited. There is one sure sign of a country’s wealth or lack of it – the amount of litter you find along its roadways.

The more prosperous a people, the more litter that is accumulated along its highways. Nigeria has tons of trash everywhere. The country is basically one big trash dump. Now there are a lot of poor people in that West African nation, but there are a lot of wealthy ones too.

Matthews Ridge, Guyana has got to be one of the poorest places on earth. Every bit of waste in the small town was recycled, not out of any great concern for the environment, but out of necessity. Empty tin cans became patches for leaky roofs or walls. Waste paper was collected and used to start cook fires.

Matthews Ridge is a formerly bustling town built near what had become depleted bauxite minds in northwest Guyana, near the frontier border with Venezuela. During its heyday, some five years before the arrival of the Jonestown Agricultural Commune in 1976, Matthews Ridge boasted a population of more than a 1000 miners and their families.[1] By the time Jonestown’s residents perished in the mass murder/suicide, the town had shrunk to about 250, mostly Amerindian residents.

The main industry of the former mining town became subsistence farming and by 1978, the farmers and their families were barely surviving. Sadly, there were more bars in Matthews Ridge than all other businesses combined.

Our aid station was set up at an airfield three miles south of Matthews Ridge. The only people living at that location was a garrison of 20 or so Guyana Defense Force soldiers who lived and worked in three small buildings situated on a small mesa overlooking the black tarmac runway. We shared a small corner of the flat hill with the GDF troopers.

There was one small building on the edge of the tarmac. It was little more than a shack with a large overhanging roof, used to shelter travelers from the weather, be it the incessant heat of the tropical sun or the persistent showers of the two four-month rainy seasons of the region. Our Army fuel specialists took over this building as their fuel station.

Two signs adorned the shack. One announced the name of the town to any transients passing through who weren’t sure where they were. The other told travelers to the region they had entered a malaria area and were required to check in with the local Malaria Control Office.

We interacted daily with the GDF soldiers whose mesa we shared and the civilians of the small town down the road. Since our daily fare of c-rations quickly became boring and the locals had never seen such foods, we managed to trade some of our military-issued meals for locally produced bread and cheese. Freshly baked Matthews Ridge bread and native cheese was still a cold meal, but at least it was a different and tasty change to our diet.

But something happened on Thanksgiving Day that made our already cordial relationship with the soldiers and civilians even friendlier. By 1800 hours, we realized our promised Thanksgiving hot dinner was not going to materialize. The thought of eating beans and franks for Thanksgiving instead of the promised turkey with all the fixings was depressing to say the least.

Our Air Force communications sergeant radioed the task force headquarters at Timheri Airport to inquire about the promised and eagerly anticipated first hot meal in Guyana that failed to appear on our table. The duty officer at headquarters promised to look into the matter. Some 30 minutes later, he informed us that apparently there had been a snafu in the delivery of our Thanksgiving dinner and the duty officer promised he would rectify the situation. He said for us to look for arrival of a holiday dinner with all the fixings the next morning. He then asked how many people were at our location and we answered honestly, eight.

The next morning, Sanborn and Bernal, two famous gourmets, were waiting impatiently at the airfield shack. Finally, at 0900 hours, a UH-1 helicopter dropped out of the sky. The bird’s crew chief motioned for Sanborn and Bernal to approach the aircraft and the two soldiers, walking briskly, bodies crouching to avoid the rotor blades, did just that. They picked up two big boxes and had to make two more trips to the chopper to pick up four more containers of food.

Six large boxes of Thanksgiving dinner for eight servicemen? We were hungry and looking forward to the promised feast, but this was a little much!

The rest of the team bound down the hill to the shack. We all brought the boxes back to the aid station. Sanborn opened the first box. It was like kids opening presents on Christmas morning. “Half pints of milk! There must be a hundred of them,” said Sanborn.

“These two boxes got TV dinners, Jeff,” said Bernal. “How many?” I asked.

“Eighty eight, I count 88,” said Fielder.

“Bunch of fruit and nuts in this box,” said Sanborn.

Snafus are not isolated incidents in the Army, but rarely is a foul up followed by a snafu as positive as this one was. We were blessed with 80 extra meals.

Sanborn and Bernal wanted to dig in and pig out. They wanted to see how big of a dent eight hungry soldiers could put in this huge cache of food. Saner heads prevailed however, after Fielder suggested we invite the local GDF garrison and some of the locals, mostly female of course, to partake in our Thanksgiving Day feast. Some of the kids were already hanging around and Fielder told them to go round up their friends for a celebration. I walked over to the GDF outpost and invited Sergeant Harper and his comrades to our holiday dinner.

So on November 24, 1978, a day after the football games were played and most Americans were finished digesting their Thanksgiving feast of the day before, eight American servicemen, far from home, taught two dozen Guyanese Defense Force soldier and twice that many local teenaged girls about one of their country’s most popular holidays. I guess the meal was not unlike the first Thanksgiving celebration more than 300 years earlier, when the colonists invited the Native Americans to share their bounty.

This gesture, which in reality was actually a way to keep good food from being wasted, solidified the friendships we already formed with the soldiers and young people of Matthews Ridge. What had begun purely by serendipity with John Wayne bars on Monday, was cemented on Friday by Specialist Fourth Class Randy Fielder, who, I’ve got to believe, did so with some degree of calculation. The young man had become very friendly with not just a few of the black beauties of Matthews Ridge during the short time he was there.

Although they had little of value to share with us, the people of Matthews Ridge gave us more than they realized. They were among the kindest and most generous folks I ever met. From the man who walked three miles from his home to the airstrip with me on that dark night, to the friends Sanborn and Fielder made, to Pauline’s grandfather and mother, everyone we came in contact with represented the finest in humankind.

One night, while I was sitting in Mrs. Pool’s bar drinking a cold Banks Beer, a young man approached me. As he took the seat next to mine, he pulled a handful of Polaroid pictures from his pocket and spread them on the bar in front of me. He told me he had shot the photos around two weeks earlier, while visiting Jonestown.

The young man was fairly clean cut. He could easily have passed for an African-American on any college campus in the States, save for his obvious Guyanese accent.

I looked began looking at the pictures before me and asked questions as I viewed each one. The minister of transportation and other politicos appeared in a few shots. The local GDF commander was in some others. A smiling Jim Jones was usually in each shot that had dignitaries in it. There were some photos that showed Jones alone with a tree or a prop. There was even a picture of a bee hive. The Jonestown band was in one of the pictures and happy dancing teenagers were in another. These images made me wonder out loud what could have caused these seemingly free-spirited American expatriates to participate in the mass murder/suicide that took their lives.

After studying and discussing each of the instant photos with the friendly owner of them, I restacked the lot of them and handed them back to the young man.

“No,no,” he said, sliding the stack back in front of me. “They are for you, a gift.”

“Oh no,” I replied, realizing the potential value of the photos. “I could not take them.”

“Please, I wish you to have them,” he said.

Not wishing to offend this earnest young man, I told him I would take the photos only if he allowed me to pay for the film. In the United States, Polaroid film was quite expensive. I could only imagine how much of a financial investment these 20 pictures might represent in Guyana.

Finally, after several minutes of protest, the young man accepted my offer of 10 American dollars for the 20 photos. After arriving back at the aid station that night, I reviewed the set of pictures and decided to try to sell them to the news media when I returned to Panama. I didn’t realize at the time the grief these Polaroids would cause me.

The duty at Matthews Ridge became so routine that boredom was the biggest challenge we had to overcome. The anticipated poisoning victims were long dead before we even arrived in Guyana. The few medical problems experienced by the GREGG team and their support personnel in Jonestown were easily managed by the Special Forces medic on the ground there.

Our days were filled with administrative duties and “make work” tasks. We inventoried supplies and equipment more in those nine days than we did in the previous nine months in Panama. I made a few day trips into Jonestown, more as a diversion than to accomplish any mission-essential task. We all became competent radio operators by assisting the two Air Force communication specialists.

Our own Mike Sanborn became the only actual medical emergency our aid station cared for during the entire nine days we stayed at Matthews Ridge and this happened on our last day at the airstrip.

It was the morning of November 28, the final day the GREGG team would be in Jonestown. The remains of all the adult victims and two-thirds of the children had already been removed from the commune. We had been alerted early that morning that an aircraft would arrive in the early afternoon to transport us and our equipment to Timheri Airport in Georgetown.

As soon as Bernal, who was on radio watch, informed us of our move out order, we broke down our supplies and equipment. Specialist Fourth Class Michael Sanborn, 20-years-old and endowed with more muscle than common sense, removed his field jacket and olive drab t-shirt and took down our two tents. So intent was he on going home, he didn’t heed my warning to put his shirts back on and to slow down.

Within an hour, Sanborn was noticeably ill. He perspired so profusely that his trousers were thoroughly soaked in sweat. He appeared very weak and pale. I ordered the young medic to sit in the shade of our sleep tent that was still standing. His skin was cool and clammy and his blood pressure was extremely low.

I also noted that Sanborn’s entire torso and arms were covered with small, red, raised lesions. He obviously was suffering from heat exhaustion complicated by miliaria rubra, or what is commonly called “prickly heat” or “heat rash.”

Either problem alone can be easily managed. While heat exhaustion is a debilitating medical problem, when properly treated with rest and oral fluids, it is quickly reversed. However, when complicated by maliaria, which inhibits the sweat glands from functioning to cool the body properly, the combination of conditions constitute a possible life-threatening medical emergency.

I instructed Randy Fielder to cool Sanborn with tepid sponge baths and to offer him as much cool water as he coud drink. I told Sam Bernal to prepare an intravenous infusion of normal saline for Sanborn while I went to the radio to consult with our brigade surgeon, Major Burgos, at Timheri Airport.

Once we contacted the task force headquarters, the communications specialist there told us to wait while he sent for a doctor from the medical clearing station that was set up there. After about ten minutes that seemed like an eternity, the distant voice of a physician I didn’t know came through the speaker of our radio. While the quality of the voice was understandable, the doctor’s speech had an unmistakable slur to it that told me the good doctor had been imbibing at this early hour of the day.

“Thish ish Doctor Winston, how can I hep you?” said the tinny voice.

“Say ‘over,’ sir” prompted the communications specialist at the airport 150 miles away. “Over,” added the physician, obviously unfamiliar with radio protocol.

“Doctor,” I said, “I have an otherwise healthy, conscious 20-year-old Caucasian male with symptoms of severe heat exhaustion complicated by miliaria rubra of the trunk and arms.”

Worried that the quality of the radio speaker might cause the already mentally impaired physician to misunderstand what I was saying, I spelled the condition phonetically, “That’s miliaria, MIKE-INDIA-LIMA-INDIA-ALPHA-ROMEO-INDIA-ALPHA, over.”

There was a long pause from the Timheri Airport end of the radio call. I continued with my message: “His temperature is normal, pulse is 122, respirations 32, blood pressure 92 over 40. I have begun cooling the patient. We are giving him oral fluids and having him lay in the shade with his legs elevated. We have just started an IV of normal saline. Do you have any other instructions? Over.” The words were presented over the radio in slow distinct segments so the radio man could copy them down.

“What did you say he hash?” queried Doctor Winston.

“Say ‘over,’ sir,” coached the exasperated radioman.

“Over.”

“He has heat exhaustion and miliaria, I spell phonetically, MIKE-INDIA-LIMA-INDIA-ALPHA-ROMEO-INDIA-ALPHA, over,” I replied clearly and slowly. There was another long pause.

After what seemed like five minutes, but what was probably more like two, Doctor Winston’s beery voice boomed over the speaker of our radio. “Have him rest. Give him water to drink and start an IV. I want you to bring the patient here. Over,” he said in a slurred but authoritative voice.

While the Air Force communications sergeant arranged an air evacuation for Mike, I met quickly with Sam and Randy. Most of our equipment and supplies had already been packed and palletized. There was nothing left to do but take down one tent and wait for transportation to arrive. I told my two comrades I would accompany Sanborn to the clearing station at Timheri Airport.

Within 30 minutes, an Army U-21 arrived to transport Sanborn and me out of Matthews Ridge. While winging our way toward the airport, 150 miles away, I noticed the speed of the aircraft was well into the red warning area on the control panel speed gauge. I told the pilot that our emergency was not so severe that he had to risk flying faster than was safe, and he told me to take care of my patient and he would take care of flying the plane.

We did arrive safely at Timheri Airport. Medics from the clearing station sent down from Fort Bragg, North Carolina, met us and took Sanborn to a waiting field ambulance for transport to the medical units Admission & Disposition Section. I saw Captain Skinner and Major Burgos standing in an open doorway at the old terminal building, so I walked over to them to give them a report.

As I related the details of Sanborn’s heat injury and the difficult time I had communicating with the clearing station physician, an obviously soused Army lieutenant colonel physician approached and asked if I was the medic who brought the patient with the heat injury. I acknowledged I was and the arrogant doctor with the drinking problem looked at me and said derisively, “He doesn’t have malaria, he has a heat rash!”

All I could manage to respond was, “Yes sir, thank you sir, I’ve learned a lot from you today.” The tipsy doctor turned around and stumbled back to his clearing station.“He’s been like this every day,” said Major Burgos, by way of explaining Doctor Winston’s behavior.

[1] Tim Merrill, Ibid.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment